Video Advertising Best Practices

If you're unsure which platforms perform the best or how to create the most visually stunning video, here are the video advertising best practices.

Read More

A skate shop, perhaps the most successful skate shop in the history of the world, owned by a man who doesn’t skate and doesn’t care much for the sport. A brand that doesn’t classify anything as limited, but only releases short runs and never re-releases product. A fashion icon that swears it’s not a fashion brand. Supreme is an intriguing, tangled web of contradictions.

Maybe that’s why the brand was able to rise to such cultural significance: in a certain light, it’s hard to tell the difference between “hot mess” and authenticity. If you color outside the lines long enough, you lose the ability to tell where truth ends and myth-making begins. And maybe that’s all anyone really wants out of a brand; maybe we want something that appears messy enough that, just for a moment, we suspend disbelief and think maybe this is all one big accident and not the result of years of calculated brand building.

In the early 1990s, James Jebbia was a burgeoning fashionista in New York City’s underground scene, who worked his way up the ranks at Parachute and opened the proto-streetwear stores Union NYC and Stussy — the latter with surfer and surf-wear pioneer Shawn Stussy. Then, with Stussy leaving the retail game, Jebbia was looking for his next big move and found it in a storefront on Lafayette Street.

Supreme's First Store in NYC

Supreme opened in 1994 with a staff of edgy, anti-commercial kids with attitude. They were confident, fearless, opinionated, and unapologetically authentic — traits that carried into the overall energy in and around the store. It was intimidating, yet intriguing — and ultimately the workings of Supreme’s cult-like appeal.

They threw together a logo to meet a t-shirt print run deadline, and an inventory that was best described as “sporadic.” The store cultivated a minimalist aesthetic, which was good because in the early days before digital inventory management and AI-powered sales projections, and before Supreme was valued at $1 billion USD, keeping the store stocked with board decks and t-shirts was a challenge. The store would either run into cash crunches and be hard-pressed to fill shelves or would order small quantities out of fear of being stuck with poorly selling merchandise.

The store was a hit almost immediately. Jebbia, taking advantage of connections made at Parachute, Union, and Stussy, brought in a ragtag gang of socialites, artists, musicians, and even the occasional real skateboarder, who would come to the store to hang out as much as to shop. It became a sort of modern-day Parisian cafe, a place where one could come to have a conversation about Puff Daddy and Patssi Valdez, all while enjoying a discreet beer or malt liquor.

From these humble roots, Supreme grew into an empire that now spans 11 locations, publications and visual art, and the top prize for menswear at the 2018 Council of Fashion Designers of America Awards. Along the way, it has collaborated with iconic brands like Louis Vuitton and Comme des Garçons, and iconic personalities like Lady Gaga and Lou Reed. But how did it get here? What’s the brand’s secret sauce?

It’s easy to look at overall trends and say, “Streetwear is being driven by growth in luxury product demand.” After all, in 2018, Bain & Co. estimated the personal luxury goods market to exceed €275 billion. But the reality is much more complex — dig a little deeper and you see that much of that growth is actually being driven BY streetwear. The rise is largely being pushed by a confluence of these social and economic factors.

A lot of what’s pushing the streetwear market may sound familiar to anyone who’s read our Unrolling: White Claw article. One of the main drivers is the growth of income inequality across much of the world. A survey from streetwear chroniclers Hypebeast and Strategy& (the young, hip arm of PWC) found 70% of streetwear consumers have incomes of $40,000 or lower. That’s well below the U.S. median household income of ~$64,000, and a far cry from the usual fashion consumer browsing Barney’s or shopping at Saks Fifth Avenue.

These shoppers, mostly in their mid-20’s, have found themselves somewhat boxed in. On the one hand, the “jobless” recovery after the 2008 recession has left many young people, particularly young men, feeling a steady pressure of wage stagnation and rising costs. On the other hand, the proliferation of social media — especially Instagram — has made it nearly impossible to avoid seeing how “the other side” lives. Young adults are being sandwiched between gross consumerism and the gig economy, falling wages and rising FOMO (fear of missing out). Streetwear, with its myriad limited releases and surprise “drops” (product releases), allows for a feeling of exclusivity and cachet without the soaring price tags of legacy designer labels.

This is another one that may sound familiar to Unrolling: White Claw readers. Despite its roots in the hypermasculine worlds of the 1980s/1990s skateboarding and hip hop culture, streetwear has largely been at the forefront of a kind of post-gender and post-racial identity. While some brands have drawn criticism for being a “boys’ club,” the general trend in streetwear has been towards inclusivity and a kind of unassuming wokeness that eschews labels. Fashion has always elevated a kind of androgyny in the models they used, but many streetwear brands take it a step further, pushing back against the very idea of “menswear” or “womenswear.”

The challenge of identity and what it means has been bubbling over for as long as people have asked “who am I?”, but it has come to a head in recent years as millennials and members of Gen Z seek to redefine themselves in terms of their style rather than their demographics.

Supreme’s first outposts outside of New York were in Japan, and it has been embroiled in a monumental battle to gain control over its trademark in China. Asia has become a dominant market over the last decade, and especially in personal luxury goods. The Bain report linked above estimates growth of up to 25% in demand by Chinese consumers for fashion, with much of that being driven by streetwear. Other developing markets are not far behind, with Southeast Asia, Eastern Europe, and Latin America marking strong growth personal luxury consumption.

Streetwear has seen tremendous success in these areas for the same reason it has seen strong growth in Western Europe and North America — it offers the exclusivity and “street cred” of legacy luxury brands, but often at a fraction of the price. For a growing middle class anxious to show off their new status, streetwear represents a near-perfect intersection of price point and prestige.

With streetwear breaking out into the mainstream, it’s easy to write off Supreme’s rise as simply being in the right place at the right time. Doing so, however, ignores the decades of hard work and brilliant marketing that the brand has put in to get where they are. Supreme isn’t on top because they caught the wave and rode it — they are the wave, and have pioneered most of what we associate with streetwear fashion and culture.

Supreme San Francisco Opening

Take the “drop” — an often spontaneous (though occasionally scheduled) release of new products, with the actual contents of the release a closely guarded secret. These drops have come to define streetwear and sneakerhead culture, with brands from Nike to Gucci holding events at which they parcel out carefully controlled quantities of new releases to lines of adoring fans. Supreme pioneered the approach, initially writing it off as the struggle of a small business to stock inventory, but eventually making these limited release events a core part of their business model.

Relying on an artificial scarcity model has given Supreme the ability to keep prices low (relative to legacy fashion brands like Gucci and Louis Vuitton), while still providing the exclusive feeling of higher-tier luxury goods. More than that, it has become its own marketing — rather than having launch parties for new collections twice a year, Supreme has managed to turn their Thursday "drop" into a can't-miss event. One filled not with press, influencers, and industry insiders, but with loyal fans who accomplish the same task as the former (spreading awareness and hype about the brand) without needing to be bribed with open bars and hors d'oeuvres.

The collab (collaboration) is another streetwear staple that was formalized by Supreme. Perhaps owing to their close proximity to the art and outsider couture hub of New York in the 1990s, or perhaps thanks to Jebbia’s keen eye for cross-promotional opportunities, Supreme has a long history of partnering with incredible people and brands. Their style of Supreme X Brand collabs has been aped by just about every fashion brand in existence at this point, but in the late 90’s it was almost unheard of in mainstream culture. From skateboard decks designed by Damien Hirst to Lou Reed t-shirts, the brand has managed to carve a wide swath through underground culture far beyond their center as skatewear.

Amazingly, Supreme has managed to create a unique and cohesive voice by borrowing heavily from others and then reimagining the zeitgeist. Even their iconic logo, the bright red box (#FF001B) with the bold white text (Futura), is a design that either borrows or steals, depending on who you ask, from contemporary feminist artist Barbara Kruger. Many of their products feature the works of others, remixed and mashed up, to form a sort of circular in-joke at the expense of culture. Supreme is rarely the first to a product category, and they’re rarely the best at it, but the end result is always unique and stands apart from the thing it imitates — even if it’s the exact same product.

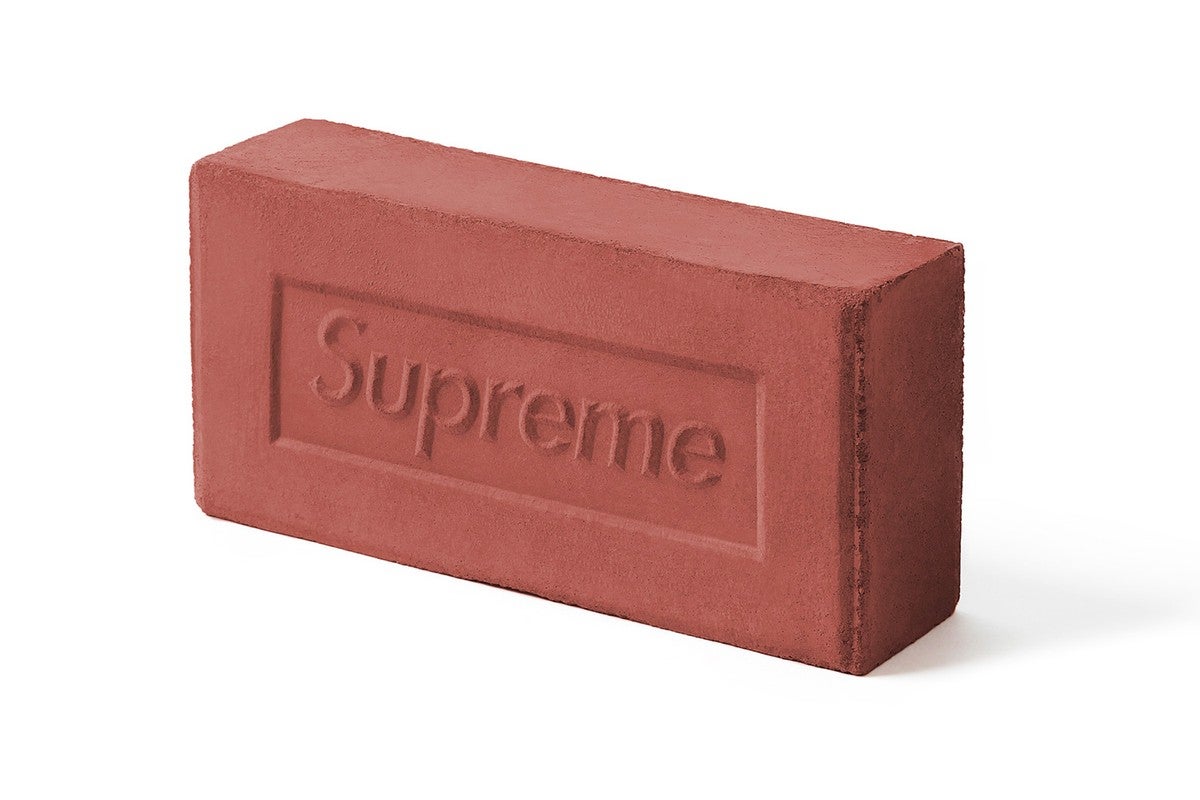

But perhaps the biggest contributor to their success is their intense dedication to doing things their way and their way only. From their start in 1994, when they pioneered customer service by refusing to provide any, to their eclectic but choosy approach in deciding who they work with, to the audacity of selling a brick for hundreds of dollars, Supreme has always done things one way: Jebbia’s. Call it authenticity, or hard-headedness, or megalomania, or heritage, Supreme has created one of the few truly global and far-reaching brands that can draw a clear line from what is on their shelves right now to what was on their shelves the day they opened. That’s not to say that Supreme doesn’t pay attention to trends or shift with the times. They do, but they do so with a dogged determination to never venture too far from the comfort of their past.

The Infamous Supreme Brick

That refusal to change the core of the Supreme brand extends to its marketing. Supreme, despite being valued at $1 billion USD, spends almost no money on marketing or advertising. Barring a few poster campaigns and some collaborations with celebrities, Supreme doesn’t advertise in any way. Instead, it relies on its legions of fans to evangelize on their behalf, spurred on by drops and collabs and the air of a closely guarded insiders club.

Supreme has managed to build a juggernaut by looking at the retail playbook and then proceeding to do everything differently. Their retail staff was unwelcoming. Their products priced higher than similar competitors. Their inventory model was built on not having things in stock. They don’t advertise or play nice with the press. And yet, they’ve managed to not simply survive but thrive. Here are the lessons of Supreme:

Last updated on February 28th, 2026.